“Crisis will force the next enlightenment. We … should do a lot more to synthesize the humanities with science … We are doing very well in science and technology. … But let’s also promote the humanities, that which makes us human, and not use science to mess around with the wellspring of this, the absolute and unique potential of the human future.” E.O. Wilson

A strong case can be made that during the Middle Paleolithic age, approximately 70 thousand years ago, a seismic shift happened in the evolution of our species. Our ancestors, experiencing the threat of climate catastrophe, were compelled to make new advances as a prosocial species if they were to survive a very real threat in their day. Essentially, a new level of cooperation and collaboration would need to unfold if the Homo genus were to survive the Fifth Great Extinction. Evidence of this process being important is not only identified in archeological data, but in the inexplicable expansion of the neocortex of our species. Within the scope of Bowen theory, this might be understood as the most notable change in our species level of differentiation. Homo sapiens went from a species nearing extinction to becoming a dominant life form on the planet.

Defining and organizing ourselves into interdependent social networks, where we could retain individuality in the midst of more togetherness, we developed a more robust set of social values so that we could manage the natural stress of living together in close proximity. It would take many thousands of years before we learned how to domesticate flora and fauna, but we were now on the way to forming a complex social culture. While the more exact details of this evolution remain somewhat obscure, the overarching trend is evident. As we became more organized as a people, we developed formal or informal institutions to insure best practices. These institutions, from the family to social governing, depended increasingly on the development of leaders to protect community cohesion in the midst of achieving advanced development. One important social institution was constituted by religious leaders who were charged with the task of protecting and applying the culture’s core values for daily living. This was the institute of religion, which evolved cross-culturally with some variation, and yet with remarkable common themes.

The Neolithic revolution, beginning perhaps around twelve thousand years ago, represents a first tipping point in which our species would begin to experience documented levels of chronic stress that translated into levels of unresolved anxiety and/or societal regression that could translate into physical illness, emotional distress, and/or social malaise. There appears, in the later historical writings of this period, evidence that religious practices were now being misconstrued and/or misappropriated by political leaders to sustain control of the population so that these political leaders might maintain an elevated social position that no longer was in service to the community as a whole.

From this point forward, the evolution of religious practice is checkered; that is, at various twist and turns, popular social leaders tended to impose their own expression on religious practice so to address their own agenda on the larger population. So, for example, it became necessary to execute Jesus of Nazareth only to formally adopt Christianity three centuries later in a version that might secure the Roman Pax. This tendency to manipulate religious practice, quite inadvertently, inspired new religious leaders to emerge so to reform or realign the direction of religious development. This is the simplest way to understand the rise of the Abrahamic tradition leading to the dominant religious traditions of our present day. Realizing that significant religious leaders come and go, sacred texts were developed to create canons that would function as a governor of religious practice. Moving forward, that which was most noble in human endeavors often fell in the category of religious aspirations. At the same time, that which was most corrupt in human selfishness also fell in the category of religious manipulation.

Just to be clear, there is an instinctual force within us searching for meaning in life, as well as an effort to identify that which is ‘ultimate’. No institution is needed to stimulate this quest. Organized religious traditions emerged, however, as a social institution to protect and advance that which the people had come to claim as ultimate. The raison d’être of the Christian Church, for example, was never about winning popularity or gaining control of the culture, but to protect and apply the Jesus Story for the present generation; a story that was so challenging to many social leaders that disciples of the Jesus Story were willing to sacrifice for the community’s greater good. The early Church was anything but popular and prosperous, but for a small community it was effective in finding a way when there was no way.

The Modern Era

During the late 19th century, in the West, there occurred another step forward in the process of humanity’s effort toward differentiation and self-organization, while honoring the communal whole. There had been enough insanity and suffering initiated by both the institutions of Church and State, each fearful of their own demise, that a significant number of our European ancestors generated a cry for reason that permeated the worlds of both the arts and the sciences. This insanity and suffering is best understood as chronic anxiety governing the culture’s most preeminent social institutions – the Church and State. Europe had reached its limit in terms of population growth, the occurrence of natural disease, and the perpetuation of warfare, such that a host of individuals began, rather simultaneously, a collective defiance against the orthodox Church and State, and pursued truth with a new measure of individual objectivity. Epitomized by

Charles Darwin and Albert Schweitzer, this new approach to discerning ‘truth’ was being perfected such that ‘ancient wisdom’ was retained only in so far as it confirmed what was verifiable in the present day by human reason.

There is broad awareness around the work of Charles Darwin as this age of Enlightenment began to grant authority to new thinkers who were breaking from conventional ideas of human development. The authority of new scientific discoveries, based on objective observation, slowly evolved over the next two centuries. Scientific inquiry has by no means secured human utopia, though at times we, as a species, has functioned as if the scientific method is a ‘panacea’. There is less understanding around the work of Albert Schweitzer, and the degree to which objective analysis was been applied to the ‘arts’, so to gain a more accurate understanding of life. At our best, social learning unfolds in each of these ‘schools’ (Arts and Sciences); however, in seasons of anxiety these two are pitted against the other as individual leaders pursue their own agenda.

During this critical period of the late 19th century, our Western ancestors brought forth both the scientific method and what we call biblical criticism. While each of these methods of inquiry were controversial, each revolutionized our way of discerning truth. Moving forward, gifted individuals made use of their ability to think more objectively, and to challenge the larger world to see life in new ways. Each of these methods represented an arduous effort to leave behind our more subjective nature, forming established ‘tradition’, so to focus on what is observable in the real world.

According to Wikipedia, biblical criticism is based on the “scientific concern to avoid dogma and bias by applying a neutral, non–sectarian, reason-based judgment to the study of the Bible.” This way of understanding sacred text pursued the “reconstruction of the historical events behind the texts, as well as the history of how the texts themselves developed.” Said more simply, biblical criticism was an effort to become more objective in our understanding of religious practice. No longer did scholars feel captive to those ‘truths’ (dogmas) espoused by the institution of the Church, and especially the ‘infallibility’ of her leader, the Pope.

Albert Schweitzer, before he entered medical school, was alarmed by the subjectivity that so many ‘experts’ brought to the study of scripture. Even academicians seemed fully capable of reading diverse meaning into particular texts. However, there was also a positivist school that had been developing for decades, if not centuries, which affirmed that a student of sacred text could move beyond this subjective tendency in interpretation of the text. Schweitzer’s book, The Quest for the Historical Jesus, was landmark, in part, because of his assertion that core values, regarding human behavior, were at the heart of the gospels. He wrote,

“In order to make the Kingdom of God a practical reality, it was necessary for Him [Jesus] to dissociate it from all the forces of this world, and to bring morality and religion into the closest connection. “The law of love was the indissoluble bond by which Jesus forever united morality with religion.” “Moral instruction was the principal content and the very essence of all His discourses.” His efforts “were directed to the establishment of a purely ethical organization.”

Biblical criticism not only challenged traditional doctrines put forth by ecclesiastical leaders, but re-established human behavior, and therefore religious practice, as the cornerstone of religious evolution. Said another way, Schweitzer was affirming that the central focus of the biblical text was not about eccentric church doctrine or dogma, but observable human behavior; it was relational as opposed to ideological. This clarification in understanding religious practice did not, of course, generate utopia; in fact, in the short-term it gave birth to its antithesis – fundamentalism. In the era in which biblical criticism rose as a dominant mode of studying scripture in our Seminaries, there was this equal and opposite emotionally reactive response in which those who felt threatened by biblical criticism began an aggressive campaign to illuminate those who wished to us reason over revelation. Revelation, often in the eye of the beholder, was the ‘only true interpretation’ of sacred text.

The Explicit vs. the Implicit

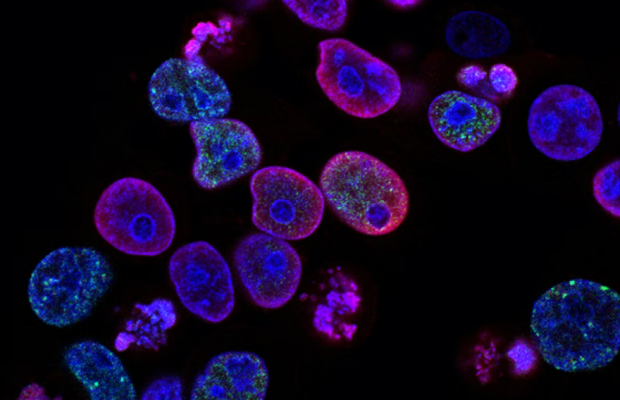

The essential point being made here is that the Enlightenment encouraged a new level of objectivity in all spheres of learning. A great deal of learning happens explicitly, especially in the classroom or laboratory, in which great pains are taken to objectively observe the natural world under the peer review of the larger community. Established learning is affirmed as theory. In a more formal way, this is referred to as the scientific method. However, there has always been a tangential way of learning, that is, through implicit learning. The case can be made that most learning, in both the human and more-than-human world, unfolds in this slow, non-conscious process. Implicit leaning happens as our senses scan the natural world, often non-consciously, and come to recognize patterns, methods or trends that generate adaptability for a species. Flora

‘learns’ to adapt to the environment through the use of fungi to share essential nutrients. Young children learn a great deal by quietly scanning the social world and discerning those life patterns that enhance adaptability with the larger world. Children who are not able to scan and learn social lessons may be diagnosed as autistic. Social mores are primarily learned implicitly with feedback from parental figures. In more mature families, this feedback is quite helpful. In more chaotic families, children learn behavior that will ultimately prove to be problematic, such that they become symptomatic of the anxiety present in their family of origin.

The Enlightenment, or modern era, did not create the hoped-for human utopia. The industrial revolution has created tools that can be both ingenious and horrific. Climate change is an excellent example of how chronic anxiety has led to functional systems that endanger life; that is, how an anxious pursuit of convenience and comfort resulted in environmental degradation. Nevertheless, there remains this possibility to develop our implicit learning system over many generations. Alongside societal emotional process, which may produce toxicity, there remains an instinctual system to use our implicit learning, to develop healthier life patterns. It now appears that humanity is going to learn new life patterns, as opposed to mere industrial development, that will be more promising to the biosphere. The only question is whether we will learn these behaviors soon enough to effect a change that will save our species.

The point here is that implicit learning, while not as quick as explicit learning, is just as important, if not more important, in the process of differentiation and self-organization. Explicit learning may be effective in a single lifetime, while implicit learning happens over a much greater time span. For instance, it may be that after more than 300 years of emotional reactivity, European Americans are finally gravitating toward a relational position with both Native and African American populations that more closely aligns themselves with their core values; that is, liberty and justice for all. It has taken European Americans twelve generations of erratic behavior in order to observe and act on the chronic anxiety that has governed and harmed social relations in America. The suffering involved in racial and ethnic discrimination, over centuries, is propelling the community of European Americans to apply their moral values; that is, to differentiate and organize their community life that is in communion with the larger world, and therefore, more adaptable.

While the genre of explicit learning pervades the sciences and classroom, the genre of implicit learning is the home of religious practice; be it Western or Eastern in orientation. Biblical criticism is based on the “scientific concern to avoid dogma and bias by applying a neutral, nonsectarian, reason-based judgment to the study of the Bible” because religion evolved, largely coconsciously, as an effort to support the learned social values that were critical in terms of Homo sapiens developing the level of cooperation needed to be a prosocial species. Rudiments of these learned social values can be identified rather clearly in both the Great apes and Cetaceans, indicating that our species is relatively late in learning social mores. Religious practice evolved neither as dogma nor as a mechanism to win favor with the gods, but as a relational way of life that brought our species in concert with the human community, the more-than-human world, and the greater universe. Living in awe of the universe is not peculiar to our species. However, this relational way of life represents our best effort to bring cohesion to the larger community.

While explicit and implicit learning evolved with a positive intended benefit, there remains a significant portion of human behavior guided by ‘quasi-science’ or ‘quasi-arts’ in that this thinking and behavior is governed by chronic anxiety as opposed to reality-based reason or learning. Within ‘science’, for example, there remains large support for germ theory, a reductionist cause- and-effect line of reasoning that lacks understanding of either the greater microbiome or the manner in which the larger field of life influences human health. Simplistic germ theory guided much of ‘thinking’ and response to Covid19. This misunderstanding of ‘germs’ has also resulted in less progress in the treatment of cancer. Within religion, ecclesiastical leaders, under the governance of anxiety, proposed the doctrine of discovery, which has been devastating in the realm of race relations. The Jesus Story cannot possibly be reconciled with the doctrine of discovery, and yet the Church was the key player in promoting this ‘theory’ leading to an apartheid-like treatment of Native Americans, and, most recently, to the mass incarceration of young black males.

The interface between Bowen theory and religious practice, properly understood, is that both are grounded in a more accurate, objective understanding of the real world. They represent efforts to define and actualize healthy adaptation to life. With this more reality-based understanding, both the individual and community learns to differentiate and self-organize in a fashion that honors our communal relationship to the larger world; including the more than human world and/or cosmic forces far beyond our ability to understand. While dual-process learning (explicit and implicit) was only in its infancy stage during his lifetime, this appeared to be the direction in which Bowen was moving in terms of applying natural systems theory to the whole of human learning. This is present in his comment, “I am thinking about who are the people that are important to me, rather than the ones that I am important to.” Arguably, most of what we learn does not happen in the classroom or laboratory, but in who we decide to associate with over a lifespan. It may well be that most of our learning happens not around the striving of the individual, but around the community of persons we choose to be around. In any case, the possibility of defining a self unfold most effectively as we dwell in the real world; that is, the world of both the arts and sciences.